Sveta Yamin with her parents and grandparents in front of the Odesa Opera House in 1981. Sveta grew up in Belarus and, like many Soviet families, hers would travel to Odesa for vacations. YAMIN FAMILY PHOTO ARCHIVE

Sveta Yamin with her parents and grandparents in front of the Odesa Opera House in 1981. Sveta grew up in Belarus and, like many Soviet families, hers would travel to Odesa for vacations. YAMIN FAMILY PHOTO ARCHIVE

by Sveta Yamin-Pasternak and Igor Pasternak

Winter 2022-23, FORUM Magazine

In his 1975 monograph on the importance of family for the Iñupiat of northwest Alaska, Arctic anthropologist Ernest Burch notes that “no one was ever voluntarily in a situation where no relatives are present.” For much of our lives in the former Soviet Union, the same was true for us: aunties, cousins, multigenerational households with grandparents, great-grandparents and their progeny always being within arm’s reach, a short walk down the street. Living in Fairbanks for almost a quarter century and having no relatives nearby, we have embraced the idea of fremily. For us, it’s a network of friends who are so close and dear and inspiring to each other that every fremily member is always longing for the others’ company; they’re always thinking about them, rejoicing or worrying as circumstances demand, and drawing comfort from knowing there’s nothing your fremily wouldn’t do for you just as there’s nothing you wouldn’t do for them.

Ever since Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Igor, the sole Ukrainian among our chosen kin, has been feeling the unequivocal support of our Fairbanks fremily. This affinity was especially palpable on our float in the 4th of July parade with waves and waves of yellow and blue (the Ukrainian flag’s colors), signs, and a long crowd cloth. In the lead, Sveta wore a headdress of flowers and ribbons; in the middle of the procession was Igor, driving our aging Alaskan truck with vanity plates displaying the name of his birth city, Odes(s)a; dogs rode in the back, and the song Hey, Hey, Rise Up! (a 2022 collaboration between Pink Floyd and Ukrainian singer Andriy Khlyvnyuk) was playing over the PA system mounted on the vehicle’s roof. Spectators cheered and shouted, and many of them later shared their photos; we, in turn, forwarded these to our fremily members who never leave our minds: our loved ones in Ukraine’s war zone.

Odesa’s geography and cosmopolitan population make it a meeting place for culinary traditions. Igor Pasternak visited a market stall selling dried fruit and nuts. SVETA YAMIN-PASTERNAK

The “S” in Odes(s)a: Ukraine’s Multinational Mama-City in her Layered National Dress is the title of a lecture Sveta gave a few years ago at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, where both of us teach. The talk featured dozens of images—photos taken around the city, book covers, theater and cinema posters, souvenirs—showing different spellings of the city’s name. Until recently, the Russian spelling Odessa was most often used in English. But now, the Ukrainian-based spelling in English, Odesa, is becoming predominant. The shift in the city’s spelling reflects the broader change of language in official and everyday communication in present-day Ukraine.

Both spellings have their purpose. When referencing books and other titles that use the English equivalent of Odessa’s Russian name, our spelling follows the original text. Elsewhere, we use the English equivalent of the Ukrainian spelling as a way of respecting, representing, and being part of Ukraine’s rapidly transforming language landscape. Both spellings are thus present here, varying when someone is quoted speaking in either Ukrainian or Russian.

We should also note that, regardless of their language preference, many residents use the long-known “Odes(s)a-Mama”—a fusion of a place name and a kinship term, featured prominently in public spaces, including the airport terminal.

“I want everyone I love to live here for a week and eat from the market,” reads one of Sveta’s many Facebook posts on a food experience that will always feel inimitable to her. Sharing some of the core foodways of Eastern Europe (including other regions of Ukraine), Odesan cuisine is recognized as unique not only by the city’s patriots, but through much of the ex-Soviet sphere. Odesa is a meeting place of Black Sea riches, rural Ukraine’s traditions of mushroom foraging, the country’s copious agriculture, and the Greek, Turkish, Jewish, Central Asian, Korean, Roma, and other heritages represented among the city dwellers. Accordingly, Odesa is a fertile ground for culinary fusions. The vocabularies and performances connected with all aspects of harvesting, vending, preparing, serving, and sharing food are also inextricable ingredients of its cuisine.

The city is famous for its food markets. One can spend the day roaming through row upon row of fine produce while sipping freshly squeezed pomegranate juice, taking in all the colors, and enjoying the bountiful orchard aromas permeating the air. The grand pavilions at Privoz and The New Market in Odesa are a maze of isles with artful displays of seafood and charcuterie, scandalously creamy dairy products, silky smooth paper-thin crepes, pickled and marinated deli goods, wild mushrooms, spices, dried fruit, and nuts.

Following local codes of communication and cultural expression, each product label, though it may look casually handwritten, lists every ingredient in diminutive form, emphasizing the vendor’s appreciation and innermost knowledge of what is being offered. Herring is not seld’, but selyodochka; peppers are not pertsy, but perchiki; cucumbers are ogurchiki; mushrooms of course are gribochki; and eggplants are rarely called baklazhan, as they are in the dictionary (a Russian loanword, itself likely borrowed from Turkish): instead, they’re sinen’kiye, “the cute little blue ones.”

During the months when the marine port of Odesa was making headlines, as the Russian navy blockade of the ships carrying Ukrainian grain threatened food shortages and hunger for much of the world, the vendors at the Odesa food markets—which, up to the time of writing, have remained at least partially operational—continued to tell the bloggers, journalists, and anyone else they could reach to “come to Odessa and we will make sure you eat better than you ever have.” Such a show of wartime resilience, mediated through market performances in celebration of hospitality, nourishment, and food, is quite fitting for a city with a proud tradition of making every meal a feast.

To our beloved Alaskan fremily reading this: please listen to these wise and stoic people. When Ukraine overcomes (which it will!), let us meet in Odesa for at least a week, share many jubilant laughs, and eat from the market.

Odesa’s geography and cosmopolitan population make it a meeting place for culinary traditions. Igor Pasternak visited a market stall selling dried fruit and nuts and shopped for laughs and sausage at the Privoz Market in Odesa in 2018. SVETA YAMIN-PASTERNAK

Eggplants are rarely called baklazhan, as they are in the dictionary (a Russian loanword, itself likely borrowed from Turkish): instead, they’re sinen’kiye, “the cute little blue ones.”

In the book Kaleidoscopic Odessa: History and Place in Contemporary Ukraine, anthropologist Tanya Richardson annotates a dozen-some authors who have written about the Old Horse market. Extending over the sidewalks of a crowded street, this hallowed site becomes the subject of creative prose and poetry examining the market’s vital role in the city’s life for over 200 years.

The market’s eclectic inventory includes livestock, fishing tackle, plumbing hardware, furniture, a multitude of secondhand goods, locally made crafts of all kinds, and (in a section that makes the average Western tourist feel less than comfortable) puppies, kittens, and other animals commonly kept as pets. Odesans affectionately regard the Old Horse market as one of the experiences that best represents the city. And whereas both vendors and customers at food markets elsewhere are typically adults, the Old Horse market is a gathering place for all ages while also functioning as a pet swap for a diverse group of enthusiasts, dedicated hobbyists, and other eccentric locals.

One afternoon in the year 1977, two young boys—5th grade students at the Odessa Secondary School #3—ended up keeping each other company while making their way home. Both had spent a long Sunday hustling in the Old Horse market pet row. “Mulya” (Oleg Mulberg) was dealing in aquarium fish and “Paster” (Igor Pasternak) tried his luck at selling hamsters. Both boys were semi-regulars at the Old Horse, charming the customers looking for a small pet and sometimes bartering inventory with other vendors. On this day, however, the boys found themselves undertaking a pragmatic cost-benefit analysis: what makes greater economic sense—they discussed—vending small captive rodents or saltwater fish? This is the conversation that Mulya and Paster remember forty-five years later as triggering their life-long friendship. Their enduring fremily ties have overstepped transcontinental distances and time zones—even over the last thirty years while Igor has been living in the United States. In the months since Russia’s invasion, they have made even greater efforts to be present continuously and meaningfully in each other’s lives.

At home with the Mulbergs in Odesa in 2019: Irusya, Oleg, Valya, and Kolya. PHOTOS BY SVETA YAMIN-PASTERNAK

Igor at the Old Horse market in 2016. PHOTOS BY SVETA YAMIN-PASTERNAK

Igor Pasternak (Paster) visits with Oleg Mulbert (Mulya) via phone in May 2022. Igor and Sveta were in Arnstadt, Germany, to see Oleg’s family during their stay there as refugees. Like all men ages 18-60, Oleg had to remain in Ukraine. It had been 45 years since Paster and Mulya’s bonding day at the Old Horse market. PHOTO BY SVETA YAMIN-PASTERNAK

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we visited Odesa at least once a year. The apartment where Igor grew up—in what is now regarded as the city’s old quarter—belonged to his great-grandfather, who bought it in the late 1800s. The building is within steps of the always generous, festive, and loving Mulberg family home. Just like his fellow entrepreneur from the Old Horse market days, Dr. Mulberg cherishes every moment he can spend with his wife, Iryna (Irusya), who also goes by Dr. Mulberg. Together they run a dental clinic within a block’s walk.

It was heartbreaking to witness them suffer so much this past spring, when Irusya and their children had to join millions of other Ukrainian refugees, relocating first to Moldova and then to Germany. At the earliest opportunity, we went to see them in the Thuringian town of Arnstadt. Since then, Irusya, Valya, and Kolya have returned to Odesa. Nearly every day, we chat on video once or twice at least, either during our morning/their evening or their evening/our morning.

Both Irusya and Oleg are utterly in love with their city. Like those relentless wartime food vendors, they could swear that Odesan food is better than anywhere else in the world and that life in Odesa is beautiful. Even at the backdrop of our spectacular world travels, Irusya and Oleg would still rather have all our fremily reunions in Odesa.

One time we all decided to meet in Portugal to celebrate Igor’s birthday. Igor booked a tasting menu at a Lisbon restaurant, listed in The World’s 50 Best. Meanwhile, Irusya and Oleg had arrived at our vacation rental packing a feast in two oversized shopping bags. Filled with fresh market purchases, the bags had every food group represented. They had carefully looked after every important detail. The dill and garlic, to be served with kartoshechka (the season’s freshest young potatoes), were among the highlights; even the butter (no prepackaged uniform bars here: every slab was cut and weighed on site) had to be procured from a vetted source. We still maximally enjoyed Portugal, but for our main celebration we stayed in, savoring every morsel of the diminutives so lovingly furnished by the city of Igor’s youth. This is the fremily that sprouted from the Old Horse market days of Mulya and Paster.

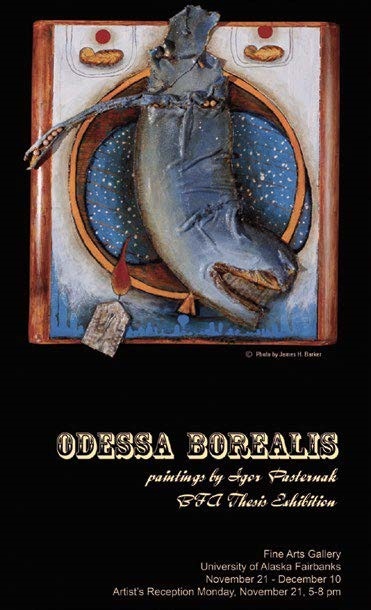

Igor Pasternak’s BFA thesis exhibition poster, 2006.

Ukraine Solidarity Float 1 at the 4th of July parade in Ester, 2022. PHOTO BY STACEY FRITZ

Sveta with her friends Lynn and Stacey during the 4th of July parade in Ester. LYNN DEFILIPPO

Odesa’s old town or historic quarter has the widest pedestrian sidewalks we have seen in any city on Earth. Shaded by the arching canopies of acacias, they are a paradise for laid-back promenades. For Sveta, who grew up in Belarus, the daily routes we take in our (nominally) adult lives are familiar from childhood: like many Soviet families, hers too would travel to Odesa for their vacations. Through the decades, the Odesa Opera House is the backdrop of the “tourist shots” in the collection of Sveta’s photos. Since the start of the war, scores of news outlets showed this eminent opera house barricaded by the bags of sand, hauled from the beach by volunteers who have done the same to protect the city’s other signature landmarks. “Odesa is Defiant. It’s also Putin’s Ultimate Target,” read a New York Times headline on August 20, 2022.

The Alaska state license plates on our truck read ODESSA and aren’t the only manifestation of Ukraine in our Alaska lives. In 2014 we did a show at the Anchorage International Gallery of Contemporary Art, which celebrated the culinary aesthetics of ex-Soviet produce farmers living in Delta Junction, many of whom are Ukrainian. As researchers, we have traveled quite a bit around different parts of Ukraine, interviewing seniors who have returned to their native hometowns at the end of their careers in the Soviet/Russian Arctic.

Back in 2006, Igor, then a University of Alaska Fairbanks BFA student, presented his thesis exhibition, entitled “Odessa Borealis.” He showed his paintings and provided the food at the opening reception, attesting to the fact that he and Sveta are citizens of the world with fremily in two homes. The “Odessa Borealis” feast was a great opportunity to teach our Fairbanks fremily the pronunciation of all the diminutives on the reception’s menu. We danced in the UAF Art Gallery until the wee hours of the night. Then and always, our cherished fremily’s support is what sends us into a state of over-the-moon euphoria.

Every Saturday beginning in March this year, we’ve been going to stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine at the Fairbanks “Democracy Corner” (the intersection of University and Geist). Smiling and waving at the passing cars, holding flags and other solidary signs, we convince each other that Ukraine will overcome, and that one day we’ll bring our Alaskan fremily to Odesa. We’ll buy everything we can get our greedy little hands on at every market stall, and we’ll have feast after feast with the determined Irusya and Oleg Mulberg. We love you so, Alaska-Ukraine fremily. Slava Uklrayine! Thank you, Alaska. It’s wonderful to have two homes. ■

Sveta, a cultural anthropologist, and Igor, an artist, both teach at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. They are currently in their 30th year as life partners.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

November 13, 2025 • MoHagani Magnetek & Polly Carr

November 12, 2025 • Becky Strub

November 10, 2025 • Jim LaBelle, Sr. & Amanda Dale