Winter 2021-22, FORUM Magazine

IN MARCH 1990, a party of six American “museum people”—curators, academics, researchers—boarded an airplane in Anchorage, bound for the Soviet Far East outpost of Provideniya. It was the era of glasnost and perestroika. The Soviet Union would dissolve as a nation 20 months later. The Americans’ trip can be measured on two timescales: the relatively brief moment of transition and turmoil in the USSR; and the immemorial span over which the Native peoples of Siberia and Alaska forged cultures, thrived, and persevered through the ebb and flow of colonial empires.

It was this longer horizon that attracted the American scholars. Taking advantage of the new openness in the USSR and travel funding from the Alaska Humanities Forum, they planned to work with their counterparts in Siberia to launch a trans-Pacific exhibition of northern Native cultures. Unlike previous efforts, the exhibition would be designed to travel to the towns and small cities in Siberia and Alaska where these cultures evolved.

Among the party were William W. Fitzhugh, a curator of anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution; Darlene Orr, director of the Carrie M. McLain Memorial Museum in Nome; and Valérie Chaussonnet, a pre-doctoral fellow also at the Smithsonian. The three recorded their impressions of the trip and of conditions in Siberia; excerpts are printed in the following pages. These were first published in the Forum’s newsletter, “Frame of Reference,” and in the catalog of the ensuing exhibition, called Crossroads Alaska/Siberia, and known to its creators as “mini-Crossroads.”

"Large-Crossroads” was Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Alaska and Siberia, a huge exhibition produced with collections from Leningrad, New York, and Washington, DC, and intended to travel to urban museums in the US and USSR. Although it toured in the US (including Anchorage) in 1988, large-Crossroads never reached the Soviet Union due to the deterioration of economic and security conditions there. Instead, the Smithsonian’s Arctic Studies Center conceived the more nimble and locally-focused exhibit, gathered allies, and embarked to Siberia on the journey of discovery.

While the team had a rudimentary itinerary and some contacts among Soviet museums, the trip turned into a marathon of opportunity. “We ended up going more places than the initial itinerary,” Chaussonnet wrote in an email. “It was a matter of getting permission to fly into locations, which was what our Soviet colleagues did for us.” Fitzhugh concurred: “We were pretty sure something would work out. Russians can be very inventive.”

Russian curators and archaeologists, facing challenges of life in economic and political uncertainty, were stimulated by the initiative, and likewise the Americans, for whom the museum collections and Indigenous knowledge of Siberia were unfamiliar. “We collaborated with numerous local scientists, many of them Alaskan and Siberian Natives, in forming the exhibit,” Chaussonnet reported. “Mini-Crossroads was a step in the direction of where the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center was heading, with a true partnership with Native Elders and researchers.”

“The project cemented many Beringian connections that developed and flourished to today,” Fitzhugh agreed.

Fitzhugh’s detailed journal of the trip is reproduced here in a condensed form that eliminates curatorial detail in favor of local color. When it appeared in the newsletter in 1990, Chaussonnet contributed an addendum to offer her somewhat different perceptions of the Soviet Union. Finally, Darlene Orr, who is Siberian Yupik and grew up on St. Lawrence Island, authored an overview of Siberian Yupik life for the exhibition catalog, published five years later.

Crossroads Alaska/Siberia was a success, traveling to a dozen towns in Alaska by 1995. An eleventh-hour dispute over Russian customs fees threatened to condemn mini-Crossroads to the fate of its larger namesake, but intervention by an Alaska trade delegation and a steep discount provided by Aeroflot secured the exhibition’s transport to Siberia, where it visited four sites in 1997.

In addition to the first research trip, the Forum supported a suite of educational materials and docent training for Alaska host museums. At the Pratt Museum in Homer, Crossroads Alaska/Siberia was accompanied by visiting Koryak (Native people of Russia’s Kamchatka peninsula) dancers and craftspeople.

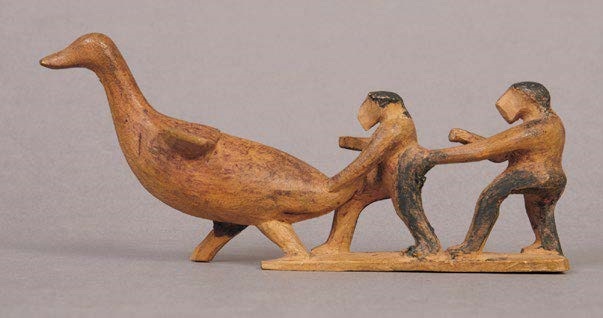

From her home in Sitka, Orr recently reflected on the trip to Russia, one of 14 she made during a career in linguistics and ethnobotany. “It was really a positive experience and trip,” she said. The team didn’t know what they would find in Siberian collections until they got there. “It was all a surprise. It was fantastic, just really incredible seeing all these objects we didn’t have access to [in the West]. We had free reign of the museums. We got to go in back, anywhere we wanted.”

Orr remembered an encounter that took place in Novosibirsk. “One of my favorite pieces was what is called the ‘Nefertiti of the Amur.’” It’s a Neolithic clay figurine, dating to 4,000–2,000 B.C., and thought to be a shaman’s helper or a household guardian. “To hold that in our hands was incredible. They gave us little replicas of it, and I still have mine.”