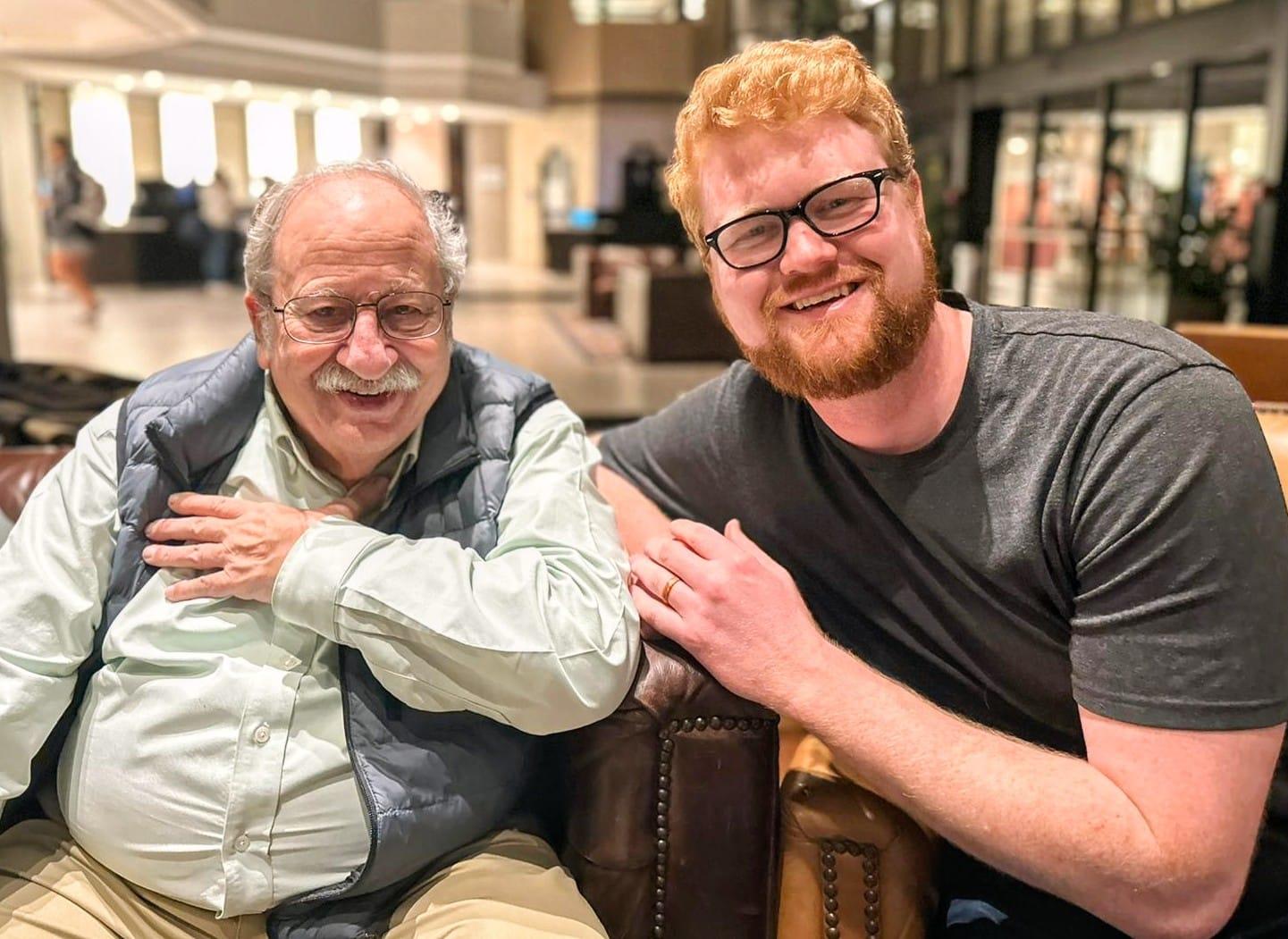

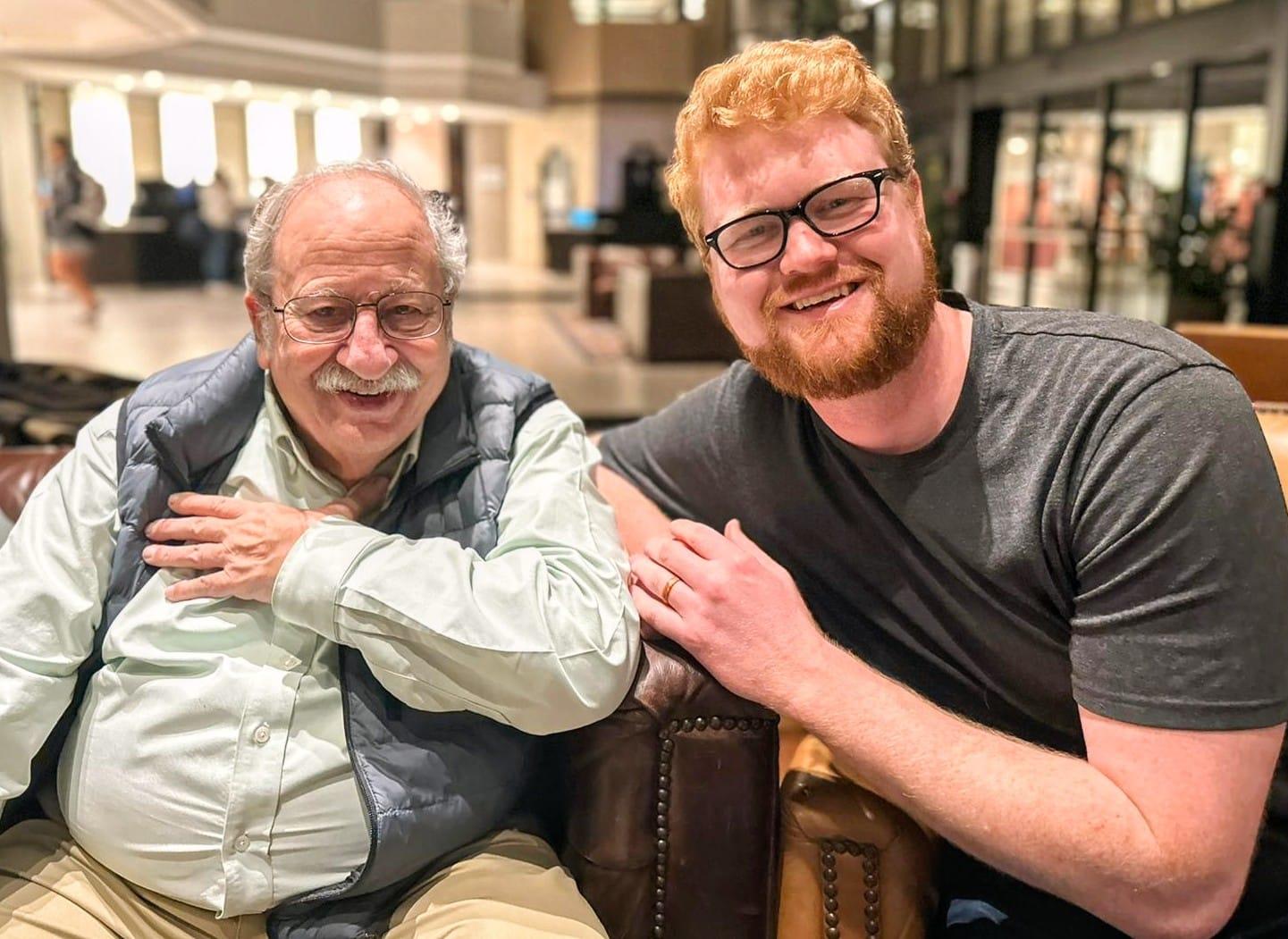

Chuck (right) with Public Narrative founder Marshall Ganz

Chuck Seaca & Amanda Dale • July 22, 2025

AKHF Director of Leadership Programs Chuck Seaca first encountered Public Narrative at age 19. Since 2017, he has led dozens of workshops around the country introducing people to the leadership practice, which uses storytelling to inspire action and build community.

This summer the Forum launched the Storytelling to Build Community workshop, which draws heavily on Public Narrative and adapts it to Alaska. We talked with Chuck about his passion for the practice, his own evolving Public Narrative story, and his hopes for the work.

What do you love about Public Narrative?

Public Narrative requires you to be real. It’s not actually a communications workshop. It’s not about, how do you polish this or say things in a charismatic way. The idea is, if you are sharing something real, you’ll share it in a compelling way.

I’m an introvert. I’m not someone who’s great at starting up a conversation from scratch. For me, Public Narrative is a permission to get to know people in a really deep way that you usually have to spend two years building up to, rather than two hours. It’s the connection and also the ability to reflect on your own life and what you want to do.

Chuck (right) with Public Narrative founder Marshall Ganz

I love that you can’t really BS your way through it. You can’t say, I really care about this thing and not back it up with choices you’ve made. Because someone will ask, what have you done to show you really care about this thing?

There’s also a lot of research that shows the process of making meaning of your own story is really beneficial to leadership development. It helps you make hard choices. I can give a really personal example here, actually.

After the DOGE cuts to AKHF in April I instinctively started to apply for a new job. Before I submitted the application, I tried to re-write my Story of Self [the first part of the three-component Public Narrative structure] with me taking a new job and realized the choice to jump ship would be violating what I care about. It wouldn’t fit with my Story of Self. You don’t jump ship in hard times. And if you have to re-build something together, you re-build something together. And that’s why this means so much to me - it’s a continual process I can use to figure out my life.

I grew up in Bethel - and as a redheaded white kid - it was far from a given that I would fit in. My first day of elementary school at Ayaprun Elitnaurvik - the Yup’ik Immersion school - was terrifying. Just the most basic start to the day - sitting in a circle criss-cross applesauce and introducing ourselves - felt impossible. Not only did I not speak a single word of Yup’ik - which was the only thing spoken at the school - but I had no clue what I was going to say when it was my turn because I had no idea how to pronounce my brand new Yup’ik name. But when it got to me - I decided I needed to at least try and introduce myself - and I butchered it - but everyone smiled and I felt a little less terrified and I eventually learned how to pronounce my name - Arrsauyaq.

- Excerpt from Chuck's Story of Self

How has Public Narrative changed how you view leadership?

I think it really reinforced how I saw leadership - or maybe gave me a language to talk about what I already believed. At its core is the idea that leadership is not about positions or titles, but about putting in the work with your community. I saw how outsiders coming into Bethel and telling people what to do with their great ideas never made a difference. There are challenges you can’t solve through technical leadership; you need people.

We need people coming together and really spending the time, doing hard work that isn’t shiny, but that over time builds real things that matter. That’s the kind of leadership I saw in Bethel - the kind I saw that worked was people who were doing community organizing without calling it community organizing. People who were just there, who always showed up for each other, who had dreams and goals and were making it work to support each other in that space.

When I think of leaders I admire, I think of people like Ayaprun [Loddie Jones], who built Ayaprun Elitnaurvik [the school] and put so much time into it. I think about my mom, who spent evenings cutting out Yup’ik translations to paste over English passages in my 6th grade social studies textbook. She has a PhD in education and never presumed she should play a high-up role in that school. You do what’s needed of you in the moment.

It’s never about giving people the answers. I am really drawn to, how do you help people figure things out for themselves and for their communities? A key part of Public Narrative is also learning how to do leadership coaching and asking questions that people have to choose their own answers to.

Public Narrative is learning how to share your own story in a way where people understand what you care about or value, sharing the story of your community so that they believe in their own power and collective commitments, and then calling on your community to join you in doing something. You’re not just sharing your own story to be seen - you’re sharing it so that you can do something. So that communities can come together. And have trust.

As an adult, I re-walked my childhood path to school. I remembered the crackling of snow on the path I had walked hundreds of times, remembered wrapping my fingers through a chain link fence, and the tears that froze on my cheeks as I looked at my old playground covered in ash from the fire that had destroyed my childhood school building.

How did you first encounter Public Narrative? How do you explain it?

I first did a Story of Self workshop with [Public Narrative founder] Marshall Ganz when I was 19. Marshall shared his own story and how it connected to his calling. Marshall’s dad was a rabbi serving children of the Holocaust in Germany, so he grew up surrounded by the horrors it had produced. He had this powerful line about how his mom always interpreted the Holocaust as a consequence of racism and that if you turn people into objects you can do anything to them. It was also the first time I’d heard someone distinguish between charity and justice. To paraphrase Marshall, “Charity is asking, ‘What’s wrong? How can I help? While Justice is asking ‘Why is this happening? How can we change it?” Marshall connected this to his calling and his choices to become a Freedom Rider and an organizer with Cesar Chavez.

For me it was a very powerful moment, seeing someone who had actually made the choices. The point of Public Narrative is it’s our choices that show our values and not just what we say. That’s different from so many speeches, the usual way people talk. We say “we value THIS” but what choices have you made that actually show you care about that? That’s where the realness is. I realized that that way of sharing your story made me feel connected to others so quickly. I knew there had to be something there.

I remember the room we were sitting in - it was this very fancy Harvard room, top floor of a building, beautiful windows, all these portraits of old white men along the wall. I could see that Marshall was living his life in a way that everyone in the room really connected with him. It didn’t feel like it so often did, when a professor who has no real world experience stands in front of a room, lecturing kids on what to do. He was someone who had literally put his own life on the line. It was so inspiring, particularly because I was trying to figure out my own place in the world.

Chuck with Ayaprun Loddie Jones. Ayaprun built his elementary school, Ayaprun Elitnaurvik Yup'ik immersion school in Bethel.

I shared how hopeless I felt and how I thought that because the fire had consumed 20 years of materials - 20 years of parents cutting and pasting and Elders sharing their knowledge to be written down - that Ayaprun Elitnaurvik was over. And then how someone sat me down and told me, “I know it hurts. But it’s a building and paper. The people are still here. We built this school before. We will do it again.”

And I realized that I had been looking for answers in the wrong place. That my community had always had what I was searching so hard for. That it was people - and people coming together and loving each other and working together that do things that matter.

The first full-day workshop I did as a student, a woman shared her story and a call to join her in supporting a refugee camp. A team came together and worked with her to make that real. So the next May, I was volunteering at a refugee camp in Greece with a group of people who’d been part of that workshop. I’ve seen real things come out of this.

I’ve also seen firsthand the power of using stories and images when you share. Two years after I first shared my story about seeing my elementary school in Bethel burn down, someone came up to me and said, “I don’t remember much about you, but I remember the scene of your fingers curling around a chain link fence as you watched the fire.” And then we connected and got to know each other better.

There are also a lot of research studies on it, but I like that at the end of a day of Public Narrative, it’s just so clear that people have such a strong desire to connect with other people and understand them. People are exhausted but they are glowing. And it’s true when people have been working together for 10 years or just met that day.

Learn more about AKHF’s Storytelling to Build Community workshops here.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

February 16, 2026 • Colleen Lomenick

January 28, 2026 • Polly Carr

January 20, 2026 • Shoshi Bieler