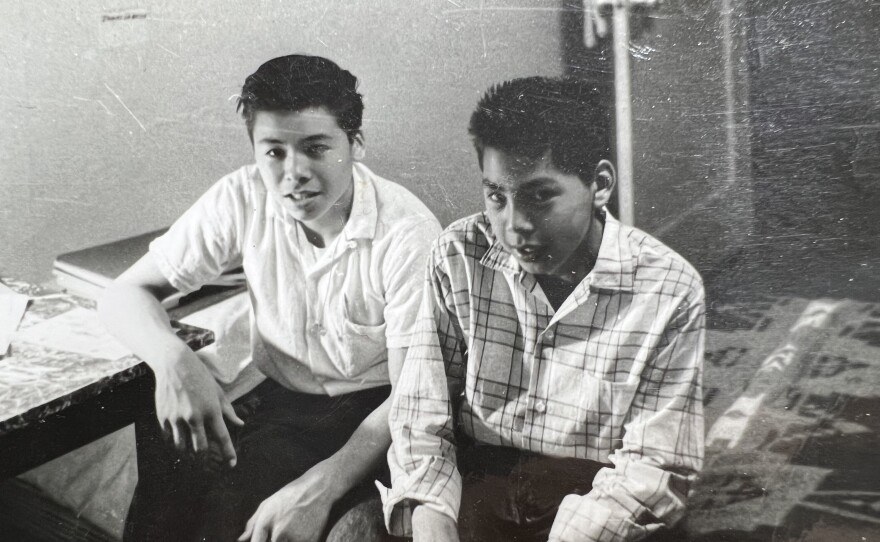

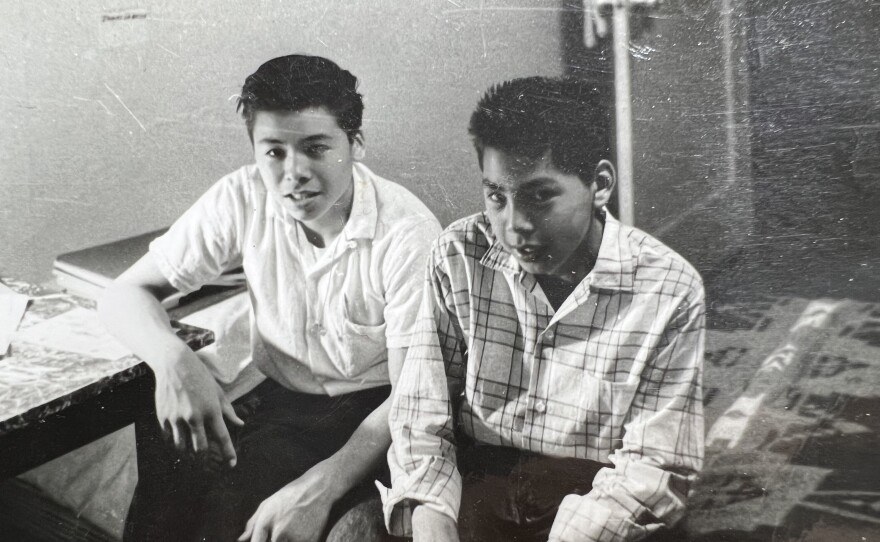

Jim & Kermit LaBelle at Mt. Edgecumbe High School Photo courtesy of Jim LaBelle

Jim LaBelle, Sr. & Amanda Dale • November 10, 2025

Do you remember a moment when you first thought, I need to start speaking about my own experiences at boarding school?

It was around 2000. I had been a part of AFN’s Wellness & Sobriety movement and we had lobbied our Congressional delegation for money to begin having sobriety programs in communities. One of the things we were able to do with that money, besides dispersing it to different regions and villages, was we had a conference where we started talking about, what are those things that are contributing to all of this - to addiction, to alcoholism, to drug use? There was a consensus that came out of that gathering: boarding school was a major contributing factor.

And that’s when it really hit me. Up until then I hadn’t really given much thought to my own 10 years of boarding school. I think it was my way of trying to deny that I had this in my background. I became kind of a workaholic and I didn’t want to live in my head for a little while. When the conference settled on this theme of boarding school as a major contributing factor to historical trauma, we had to start thinking about, how far back does it go? Some of the first children from Alaska were sent to Carlisle, Pennsylvania in the 1880s - can you imagine how long it must have taken for them to get there from say, Nome?

Jim & Kermit LaBelle at Mt. Edgecumbe High School Photo courtesy of Jim LaBelle

I went to Wrangell from 1955-1961 and then Mt. Edgecumbe from 1961-1965 and it kind of hit me, like - oh my god, I didn’t know what to say or do. I got caught up in my throat. It’s just like having such a traumatic experience you couldn’t even talk initially. That was me. And that was concerning. I thought, how am I going to continue to be involved with sobriety and wellness and say we need to heal from our historical trauma, how can I lead in this, if I can’t heal myself?

So I began my journey of trying to find ways to heal, things like talking circles and healing circles, counseling, and just telling my story. Little stories at a time. And then broadening that experience with more stories. And then I felt that I had this notion that, well, if I can do it, maybe my stories can give courage to others to tell their story. And that’s kind of been my thing all along - my story is just one, one of many. Thousands of children went through all this for many generations now. Even though it ended around 1975, some of the children were as young as five in 1975 so they’re in their 50s now. So we have a whole 2-3 generations of children - now in their 70s 80s 90s - I’m 78 - who experienced this. And I just felt, I gotta get the word out. I gotta start sharing.

Even many of our own people have denied their own experience for so many reasons. Things like, Why bring up the past? or It didn’t affect me or We’re strong. All those kinds of things. But I think we need to start looking at the things that are still with us today - the echoes of that era - to see why it’s so important. 40% of Alaska Natives are impacted by the criminal justice system but we are less than 20% of our state’s population. We have the highest rates of suicide in the country, some of the highest rates of domestic violence in the country. Here’s the shocker: over 60% of all the children in foster care in Alaska today are Alaska Native children. And those are the symptoms of historical trauma. And of course boarding schools was a major contributing factor.

I remember when you worked with the Forum’s Educator Cross-Cultural Immersion program in 2017, sharing your experiences with teachers from around the state. I remember watching their faces when they heard you talk, and how many of them were hearing about BIA boarding schools for the first time. Does that happen often?

I meet so many people who have no idea about what happened. My wife Susan and I were involved with a Quaker church group in Alaska and the Quaker church had a number of boarding schools that they controlled, including BIA day schools in Kotzebue where my brother Willie is from. We had an opportunity to talk to the descendants of this missionary group that was sent up by the Quaker church out of Oregon in the 1880s. We all told our stories and there was over 100 Quakers in the room. And you could have heard a pin drop in there.

They had this belief that what they were doing was a good thing. But in reality what they were doing was trying to erase our identity as people. These descendants expressed a lot of shock, a lot of tears. They didn’t understand that them coming up here would have that kind of an impact. So that’s an example of us having to tell someone who ran some of these schools - we are teaching them about their own history. They didn’t really know their own history.

Jim and his wife Susan with President Biden and U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland in October 2025, during Biden's historic apology for the U.S. residential boarding schools. Photo courtesy of Jim LaBelle

How do you approach your work?

I do remember when I became… well, I’m not sure what you call it but when people saw me coming, they knew what I was going to talk to them about and they tried to run away or avoid me (laughing). I’m very persistent, one by one. I worked on one gal for 20-something years… little by little I knew she could be very instrumental in helping us further this along but she was denying her own time in boarding school. But little by little I was able to get her to start talking about it, and then she - Rosita Worl - became a forceful speaker. When I heard her testify before the Alaska State Legislature, I felt like yes, all my work paid off!

There’s something about Native people... we are resilient, we are stoic, we bear things, we don’t talk about our problems. We push through. And those are the kind of attitudes I have to fight against by saying “that might have been true before Contact, but this is different.” And I also say, look at our numbers. Look at all those percentages - incarceration, foster care, DV - it had to come from somewhere. I still remember something President Kennedy said when I was a kid. He said: Success has many fathers but failure is an orphan. One of the failures I think a lot of Native people perceive is all of these problems we have. They would rather be associated with successes, wins, economic wins, contracts, employment, doing all kinds of things with culture and language. Those are all good things. But it’s at the risk of denying our history.

What else should people know about you?

All of my experiences and careers helped build up to today. A lot of folks don’t know, my early life was growing up in poverty and alcoholism and DV in my own family. And I’m proud of my military service during the Vietnam Era. I served in the US Navy and my younger brother Kermit joined the Marines about 6 months before I joined the Navy. He had 41 days left when he was killed in Vietnam. He was only 18. The Marines offered an honor guard to escort his body back to Fairbanks where we grew up and I said, I would love to be my brother’s honor guard. My commander agreed and got me orders so I could escort my brother home. I still miss him.

My wife Susan has helped me all the way along. I don’t think I could have done half of the things I’m doing without her there, helping me understand some of these things. She came from a traditional culture in her village and I grew up in a boarding school so there’s that big disconnect. She was able to educate me, and her Elders in Port Graham did, too. They were so loving. I spent many years around their coffee table and breakfast table learning all the things I should have learned growing up but didn’t have a chance because of boarding school. I’m forever grateful for that.

Congratulations to Jim on his 2025 Governor's Arts & Humanities Award for Distinguished Service in Education for his decades of work uplifting boarding school histories and supporting survivors in their individual healing processes.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

February 16, 2026 • Colleen Lomenick

January 28, 2026 • Polly Carr

January 20, 2026 • Shoshi Bieler