1 Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Headwaters People”,1990.

2 Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Porcupine”,1990.

3Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Roasted Salmon Place”,1990.

4Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Beaver fur”,1990.

5Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Thank you Creator, Thank you Black Spruce, Thank you,” 1990.

6Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Roasted Salmon Place,” 1990.

7Wilson Justin, February 29, 2024.

8Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Roasted Salmon Place,” 1990.

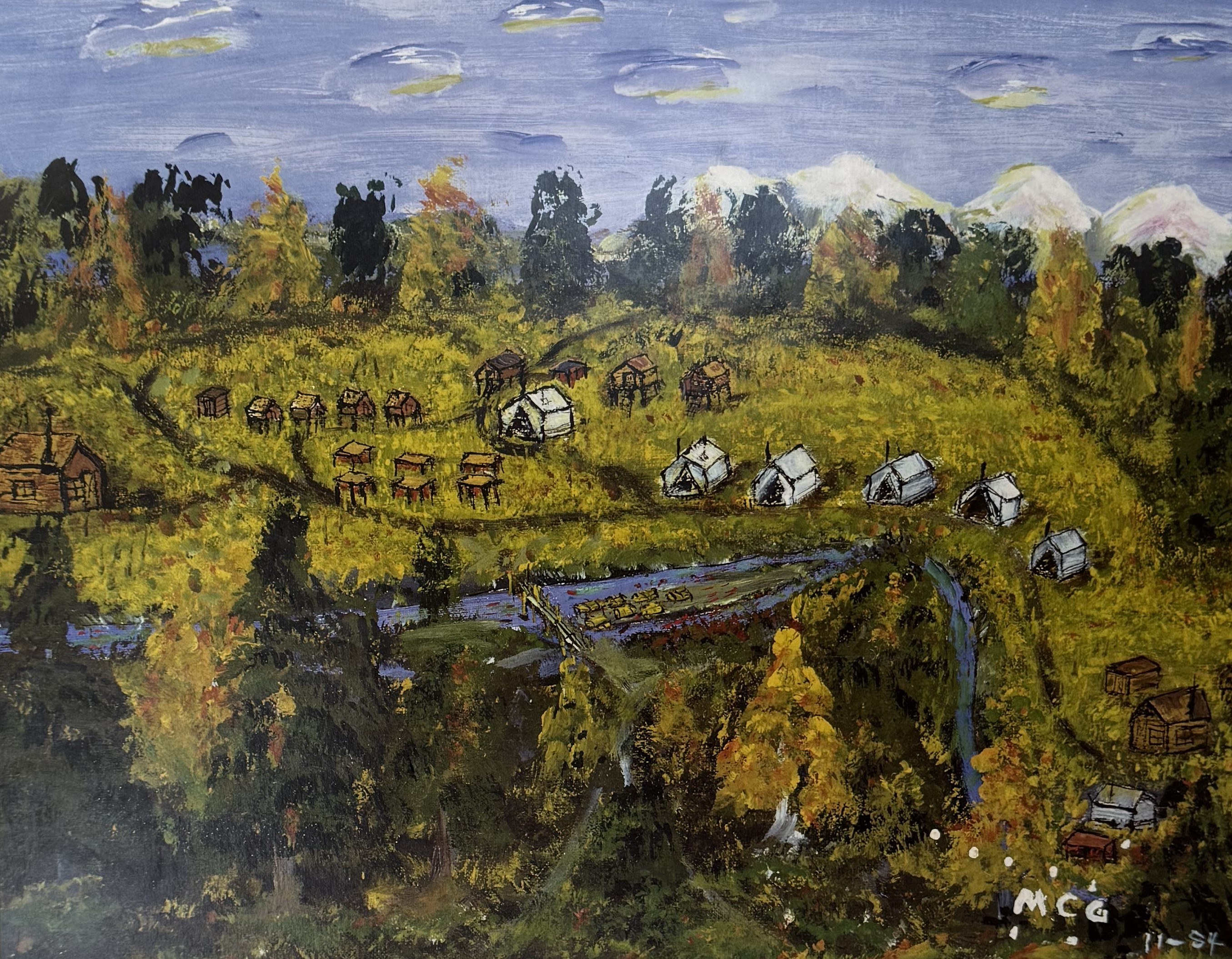

9The fishery at Nataełde was first documented on June 2 to 4 of 1885 when the Lieut. Henry Allen party met 57 people waiting for the arrival of salmon. Allen named the village “Batzulnetas” (which is locally called “Batzaneta”) for its chief and shaman, 6’4” tall Bets’ulnii Ta’ ‘father of someone who respects him’. Molly Galbreath, Katie John, James Kari 2001.

10 Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Fish weir,” 1990.

11 Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary, s.v. “Salmon,” 1990.

12 Molly Galbreath, March 5, 2025.

13 Faye Ewan, March 20, 2025.

14 The determination of what is “good” may be up to the beholder. There are social constructs at play that influence one’s judgements or thought processes of what is good. I’ve had the privilege of glimpsing the outcomes of the choice to send my great aunties to be adopted out and how it has differed from my grandma’s life. Mainly, their children are not connected to our Mentasta family, except through a distant blood memory.

15 Molly Galbreath, March 5, 2025.

16This is one of the stories passed down by my grandma and baffles me, but nonetheless the 233 mile journey was made.

17Native American Rights Fund, Vol. 6. No. 2: 2001, 2, February 28, 2025. https://narf.org/nill/document...

18“Federal Judge Allows AFN to Intervene in Case Challenging Katie John”. Alaska Federation of Natives, February 28, 2025. https://nativefederation.org/2...

19Cynthea Ainsworth, Katie John, Fred John, Mentasta Remembers, 2002, 33.

Bibliography

Ainsworth, Cynthea L., Katie John, and Fred John. Mentasta Remembers. Mentasta Lake, AK: Mentasta Traditional Council, 2002.

Ewan, Faye. Text communication, March 20, 2025

Federal Judge Allows AFN to Intervene in Case Challenging Katie John”. Alaska Federation of Natives, February 28, 2025. https://nativefederation.org/2023/10/federal-judge-allows-afn-to-intervene-in-case-challenging-katie-john/

Galbreath, Molly. In-person communication. March 19, 2025

Galbreath, Molly, Katie John, James Kari. Nataełde Łuk’ae Nilcedi: Putting Up Salmon At Batzulnetas, 2001

Justin, Wilson. Phone conversation. February 29, 2024

Kari, James. Ahtna Athabaskan Dictionary. 1991

Native American Rights Fund. “Katie John Prevails in Subsistence Fight.” 2-6, 2001.https://narf.org/nill/documents/nlr/nlr26-2.pdf