Amazed by the brilliance of the bright lights of our ancestors my son looks in astonishment from the window. Yatibaey Evans

Amazed by the brilliance of the bright lights of our ancestors my son looks in astonishment from the window. Yatibaey Evans

By Yatibaey Evans

Spring 2025, FORUM Magazine

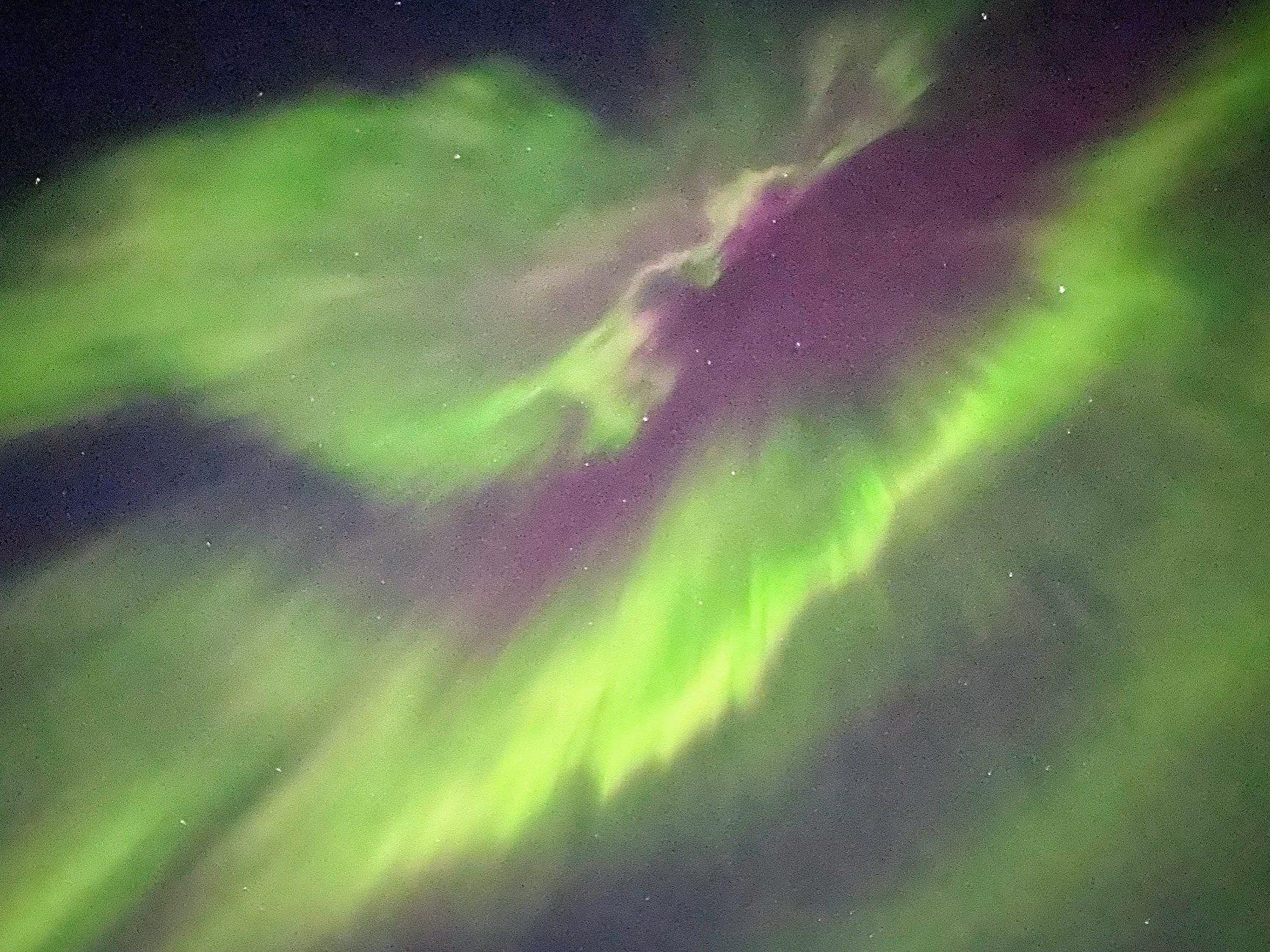

Ethereal blue, green, purple, red swirls

darkness of night.

Broken lines

organic turns

rhythmic beats

rushing in, swirling

flying across the stage

as if to say,

you cannot contain me.

Mesmerizing minds

making amends

meaningful memories

GROWING UP, the Elders used to tell us that if you whistle at the Northern Lights, they would take you away into the stars with them. My friends and I would test the idea and whistle with abandon. The Northern Lights would come sweeping down so close that it was almost as if you could hear the buzzing. We would hide away, hoping not to be drawn up into the sky. I don’t whistle at them anymore. I think there could be some truth in being swept up into the sky.

Beliefs about the Northern Lights span the imagination. People from all over the world travel to Alaska to see them. Some Indigenous cultures believe that the Aurora are our ancestors. Other people believe that it’s the ancestors playing soccer with the heads of the deceased. Writer, Dermot Cole, debunked the myth in 2018 that Japanese people have long held a belief about procreating under the Northern Lights where their child would have good fortune. Does a belief only hold if it was held from all eternity?

Scientists have discovered that the beautiful night dance phenomena are electrically charged particles created by solar flares. The first law of thermodynamics indicates that energy never dies; it transforms. We know that everything is matter and that matter is composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons. Each of these has energy, therefore, everything on Earth and in the universe has energy. And if energy never dies and it transforms, then our Indigenous beliefs could be true, the Northern Lights could be our ancestors.

Regardless of the science, energy discussion, and cultural beliefs, my parents and grandma Molly decided to name me the Mentasta language word for Northern Lights, Yatibaey (Yah-Dee-Bay). Sometimes it’s fun to tell people what my name means because of the conversations that ensue. However, growing up having such a unique name, brown skin, and big curly hair brought on hardships. In school, the teacher never knew how to pronounce my name, and then my peers would tease me. When you don’t look like everyone else or have a name like everyone else, you become an easy target for people who don’t understand the brilliance of differences. Each person has unique gifts and talents, and if we allow superficial constructs to distract us from one another’s value, we miss out on amazing opportunities for growth, connection, and relationships.

As an adult, people still mispronounce my name or want to give me a nickname. What is meaningful and kind to me is when someone stops to ask if they are pronouncing it correctly. What if we all did that? What if we took the time to “see” someone and ask them clarifying questions? We could sit with our discomfort and build a new connection. Yes, we might get it wrong again, but we are trying, we are making an effort to show respect to the person we are interacting with. Who knows, you might walk away with a brand new friend who is willing to be there for you.

Too often, we bend ourselves to fit the mold of other people. For several years of my adolescent life, I went by my legal first name, Heather. Funny thing, my family and friends always called me Yatibaey (my legal middle name), and I didn’t question my parents if I had another name. I longed to be called Christina or Jennifer, something that was “normal” and wouldn’t cause me to be teased. So finding out about my first name felt like some sort of miracle. For three years of my life, we lived in Marquette, Michigan, and I was one of three kids with brown skin. The entire school had one Native, one Black, and one Latina kid. It was like we were representatives for everyone who looked like us. Talk about pressure, misconceptions, and stereotypes. When people ask me the question, When did you first experience racism, it was at that time. That was when I first experienced “otherness”. I don’t want to paint the picture that the three of us didn’t have friends; we did, but it was rather like playing survival of the fittest. Thankfully, my parents raised me to be strong and proud of who I am. Resiliency ensued.

The boldness in my name, Heather Yatibaey Galbreath, hasn’t been easy to contend with, but it has certainly shaped me.

First day of School

Who is going to be the fool

Names written down

Looks like you ain’t from this town

Circle round

We have found another

Watch watch, I bet she’s gonna stutter

Grandma always said to stand up straight

Don’t lower your head

Remember to not take the bait

Just play it cool

Then who’s the fool

I was the new kid in school for the 3rd time. You might be thinking, “Oh, her parents were poor and they had to move around a lot.” It wasn’t like that, really. My parents both had vision, determination, and goals to get their education, so we moved where my mom was accepted to school. Changing schools and communities is not easy, no matter what socioeconomic background you come from. Many of my friends who grew up in military families know this routine all too well. You gotta make friends or you won’t make it through school. I wasn’t going to let my new schoolmates punk me. When the other kids in my class started making fun of my name on my desk and questioning me, I was like, I don’t know what that name is, my name is Heather.

By removing my name tag from my desk and putting one that people could pronounce I felt like I fit in. The circle dispersed, and the pressure was relieved momentarily. Every Heather I’ve met is a badass in her way, strong, independent, and has something to say, much like the plant that catches the eye, tantalizes the nose, and has medicinal properties. Heather is abundant where my Scottish ancestors are from, and it’s my favorite color, purple. My parents were quite thoughtful when they named me. They wanted to honor the multiple cultures I am a part of while also giving great thought to how to do this. There is so much depth to a name. I wonder if we step into our names as we grow, or if our spirits help guide parents to help name us? Perhaps a bit of both.

My parents wanted to name my siblings and me after some of the elements of life, sky, earth, and water. Mom and Dad considered naming me Sara Lothlilly Galbreath. Lothlilly means butterfly in our Ahtna language. When I think of the name Sara, I think of people who are quiet and reserved. I wonder if I were given those names, if I would have been a quiet butterfly? The boldness in my name, Heather Yatibaey Galbreath, hasn’t been easy to contend with, but it has certainly shaped me.

Going by Heather helped my survivability in 6th grade and mildly in middle school. Middle school was like going into a war without any weapons or a strategic plan, just a mission to make it. To protect myself, I would sit in the back and often stay in class until everyone else left the room. The same kid in physical education who taunted me for having my period then put a piece of string around my neck in English class. He didn’t get in trouble for it either. Could I just make it through one day without being teased, harassed, or having my life threatened?

In high school, my friends accepted me for who I was. When they came over to my house, they learned about the name my parents had given me, Yatibaey. I slowly began going by my Ahtna name, and it became a way to differentiate myself from the five other Heathers in school. I gained self-confidence in my identity. Instead of being embarrassed or not knowing how to handle the teasing or mispronunciations, I began to assert the correct way to say my name. I mostly go by Yatibaey still to this day, and have a multitude of conversations about it when I meet new people. The camaraderie with folks who have different names than many are used to, has brought a sense of connection. We swap stories about all the fumbles, as well as when we have met folks who pronounce our names correctly the very first time.

Gorgeous lights dancing early in the Fairbanks Fall night. Yatibaey Evans

Every now and then, old friends will still call me Heather. It doesn’t bother me because that’s how they met me. What is interesting, though, is when people will say Heather as a way to try to make me mad. These are often people who are or were close to me and think they can penetrate my being by calling me by my first name. While it causes me to pause, it’s only to reflect on their projected anger and allows me to see them for who they are in that moment. Oh, I see, you want to be childish. Gotcha.

When I was volunteering with a woman I had known at church for two years, she called me over, saying, “Teddybear, come hear.” I was so confused. I was like, is she giving me a term of endearment, or is this what she thinks my name is? The same number of syllables are in Teddybear as there are in Yatibaey. Teddy bear is not a common term of endearment except primarily for large, fuzzy, bearded men. Conclusion, mispronunciation. As gently as I could, I let her know my name.

To save time and energy, I sometimes will still use Heather when interacting with people I’m doing business transactions with. Once, when getting coffee with a friend, I told the barista my name is Heather. My friend Doreen commented, “That’s funny, I say my name is Jill when I order coffee.” Doreen shared that people say all kinds of different mispronunciations, so she has chosen a one-syllable name that is easier to say. I shared that Heather is legally my first name and use it when I don’t feel like explaining the meaning, the pronunciation, and any questions that might arise. I discern if the person is someone who will come into my life again, and if so, I will typically introduce myself as Yatibaey. When I meet someone and they ask about how to pronounce my name, it sends me the message that they care and are willing to take a risk in getting to know me.

Reflecting on the decision to name me such a powerful name, such as Yatibaey, and the fact that I am the last clan member from my grandma Molly’s lineage, I wonder if there is some sort of meaning in it yet to be confirmed. Perhaps Yatibaey is an acknowledgement of our ancestors and understanding that while we honor our past, we look forward to what the future will bring. It could be that it’s a message indicating that it’s okay to conclude. I’m always searching for meaning so I can put the puzzle pieces of life together. What are your thoughts about it? I guess we will all find out the answer once we transition from this earthly existence. ■

Yatibaey Evans is Ahtna, Athabascan from Mentasta, Alaska and is the proud mother of four incredible boys. Yatibaey is the Creative Producer for the Emmy Award winning PBS series, MOLLY OF DENALI. She is also an adjunct professor for the College of Indigenous Studies at UAF. Previously, she held the position of Alaska Native Education Director for the Fairbanks school district and was awarded Champion for Kids in 2021, by the Alaska's Children's Trust, A Friend of Education from Fairbanks Education Association, and Alaska's Top 40 Under 40 in 2017. Yatibaey is a 2025 FORUM Writing Fellow.

FORUM is a publication of the Alaska Humanities Forum. FORUM aims to increase public understanding of and participation in the humanities. The views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the editorial staff or the Alaska Humanities Forum.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

February 16, 2026 • Colleen Lomenick

January 28, 2026 • Polly Carr

January 20, 2026 • Shoshi Bieler