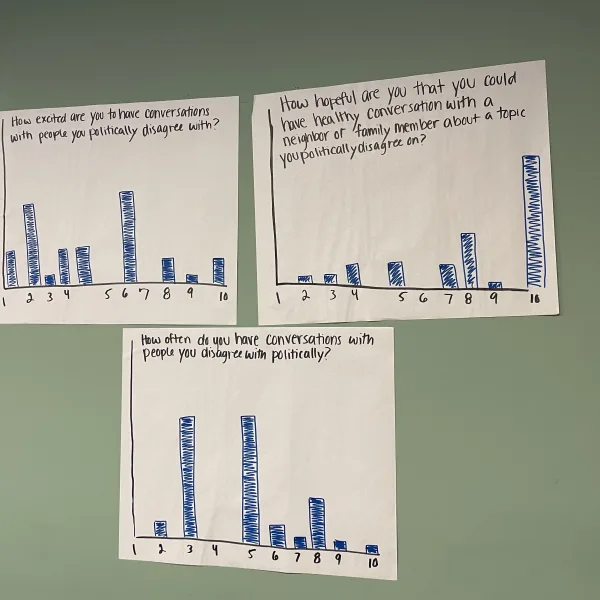

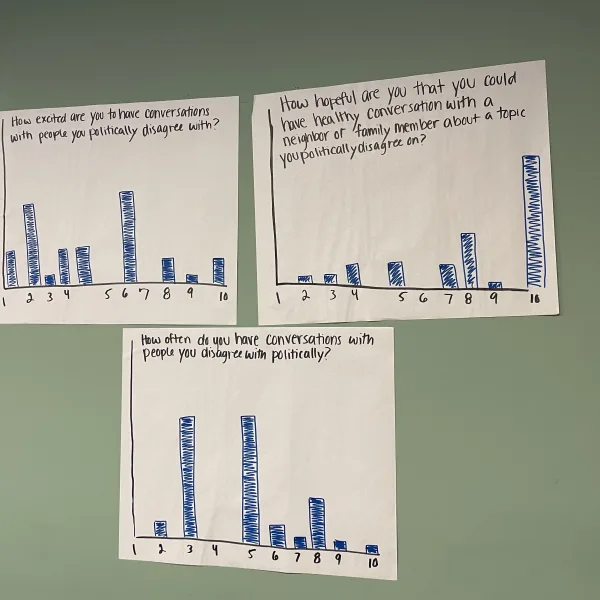

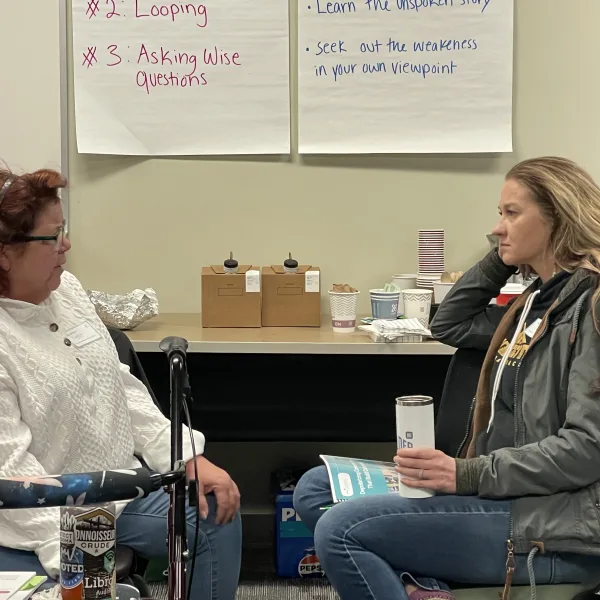

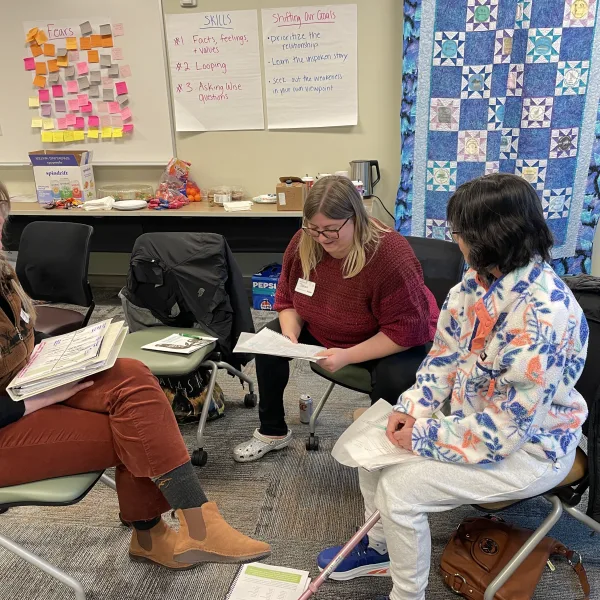

Images from Dec. 2025 Depolarizing Conversations workshop in Wasilla

Images from Dec. 2025 Depolarizing Conversations workshop in Wasilla

Images from Dec. 2025 Depolarizing Conversations workshop in Wasilla

Colleen Lomenick • February 16, 2026

Colleen Lomenick was born and raised in Minnesota, where her love for the outdoors started early. She spent her days paddling northern lakes, fishing, riding bikes around the neighborhood, skiing, and running barefoot through the woods. These experiences shaped a deep connection to the natural world.

She holds a B.A. in Psychology and Sociology of Law from the University of Minnesota, and has worked at the intersections of outdoor leadership, education, mental health, and nonprofit work. After guiding a backpacking expedition through the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, she was drawn in by the wild lands and the opportunities they offered, and in 2023, moved to Palmer to continue work in the outdoor recreation industry.

Colleen believes the outdoors is a vessel for building connections between people, communities, and the places we call home. She looks forward to creating meaningful partnerships in her role as partnerships and outreach coordinator with the Mat-Su Trails & Parks Foundation, ensuring that everyone in the Mat-Su has access to trails, parks, and outdoor spaces.

I’m revisiting this weeks after the Depolarizing Conversations to Build Community workshop, with the world feeling vivid and near. Watching events unfold in Minnesota, my home for much of my life, has brought a particular rawness to how I hold this reflection. What’s happening there mirrors the polarization many of us are living with: fear, tension, radically different interpretations of the same events. Even what we mean by safety, care, or justice can feel fractured. When we engage in these conversations, they don’t happen in isolation. They happen alongside everything else we are carrying.

This was the second gathering in a three-part cohort series, and twenty people chose to return. That alone felt meaningful. People choosing to keep showing up to sit in complexity, to practice leaning in rather than opting out.

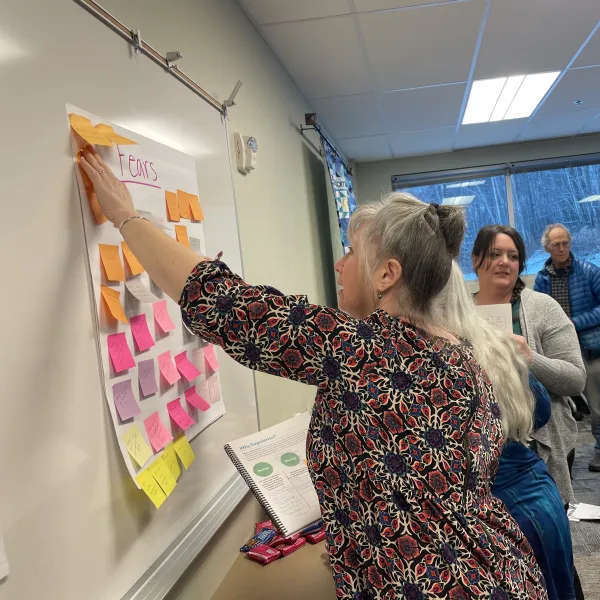

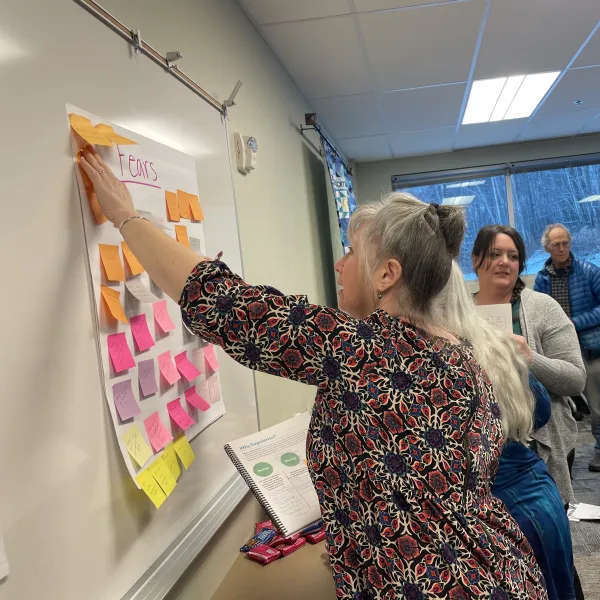

Early in the workshop, we were asked to write down our fears about being in conversations that challenge our beliefs. One by one, we added them to a large poster board. As the paper filled, the fears began to repeat and resonate.

Being overly emotional.

Finding out I’m wrong.

Feeling vulnerable.

Feeling ashamed of what I believe.

Crying.

Getting angry.

Shutting down.

What surprised many of us wasn’t the content of the fears, but how shared they were. Different backgrounds, different perspectives, and yet the same anxieties written in different handwriting. It revealed something quietly human. Beneath our positions, many of us are afraid of the same losses: control, dignity, belonging.

I’ve been thinking a lot about beliefs since then. How intimate they are. How shaped by family, culture, place, and experience. They aren’t fixed, but they aren’t endlessly fluid either. They hold contradiction, wisdom and harm, certainty and doubt, softening and bracing. When they’re challenged, it rarely feels abstract. It feels embodied. Protective. Tender.

I keep returning to the concept of bridging, as described by john a powell. Staying in relationship across difference without erasing disagreement or dehumanizing one another. I don’t hold it as a solution. I hold it with a kind of reverence, as something to practice when certainty feels unyielding and influence feels uneven. A way of asking how someone came to believe what they do, rather than trying to out argue or outperform them.

Minnesota fractured and grieving, I feel pulled by my convictions, by what I care about and what feels morally urgent. I don’t resolve it. I don’t step aside from it. And I recognize that for some, this is not a new kind of pain but a familiar ache. And yet, alongside that pull, I notice the subtle work of attention. The choice to stay, to ask, to listen without trying to erase or repair. It doesn’t make the world less fractured. It doesn’t make fear, grief, or anger disappear. But it allows space for something else to emerge. The possibility that someone, somewhere, maybe across a low-lit bar, maybe across a dinner table, maybe in a room full of community members, pauses long enough to ask, How come this became so important to you? What led you here? What have you had to leave behind to get here? What part of you feels most unseen right now?

The practice is not perfection. It is noticing. Pausing. Choosing, when we can, not to let the first reaction decide everything.

In My Grandmother’s Hands, Resmaa Menakem writes about the vagus nerve, or, as he calls it, the soul nerve, which he describes as central to how the body responds to perceived threat. Long before we have language, the body tightens, releases, moves, or freezes in an effort to protect itself. Much of this happens outside conscious control.

He emphasizes that with attention and patience, people can learn to work with these bodily responses, settling the nervous system in moments of stress rather than reflexively entering fight, flight, or freeze. For Menakem, this work is not only individual or physical but communal. The same system that governs fear is also where we experience belonging. Beneath our differences, he states, ‘each of us yearns to belong. Within each human body is this deep, raw, aching desire.’

I don’t leave this workshop feeling resolved. I leave it with a longing for a community that is not seamless, but perhaps mended. Not unified, but woven, thread by thread, held together more by willingness than agreement.

In a privileged moment of stillness and reprieve, apricity settles over me as I stand on my porch, sipping my coffee and reflecting on these words from the poem Evidence by Mary Oliver:

Where do I live? If I had no address, as many people

do not, I could nevertheless say that I lived in the

same town as the lilies of the field,

and the still waters.

Spring, and all through the neighborhood now there are

strong men tending flowers.

Beauty without purpose is beauty without virtue. But

all beautiful things, inherently, have this function,

to excite the viewers toward sublime thought.

Glory to the world, that good teacher.

Among the swans there is none called the least,

or the greatest.

I believe in kindness. Also in mischief.

Also in singing,

especially when singing is not necessarily prescribed.

As for the body, it is solid and strong and curious

and full of detail; it wants to polish itself; it

wants to love another body; it is the only vessel in

the world that can hold, in a mix of power and

sweetness: words, song, gesture, passion, ideas,

ingenuity, devotion, merriment, vanity, and virtue.

Keep some room in your heart for the unimaginable.

During the workshop, a thoughtful participant asked me if I had hope. Throat tight and eyes moist, I said I have to. Hope, I realized, isn’t optimism. It’s a devotion to something unimaginable. It’s showing up again, even when it pulls at you, even when the complexity refuses to settle. Twenty people returned, holding space to learn alongside each other, exploring the unknown. That alone keeps me here, keeps me trying, keeps me in the room long enough to feel the edges of what might be possible, to notice what emerges when we truly listen.

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

March 5, 2026 • Taylor Strelevitz

February 26, 2026 • Polly Carr

February 16, 2026 • Colleen Lomenick