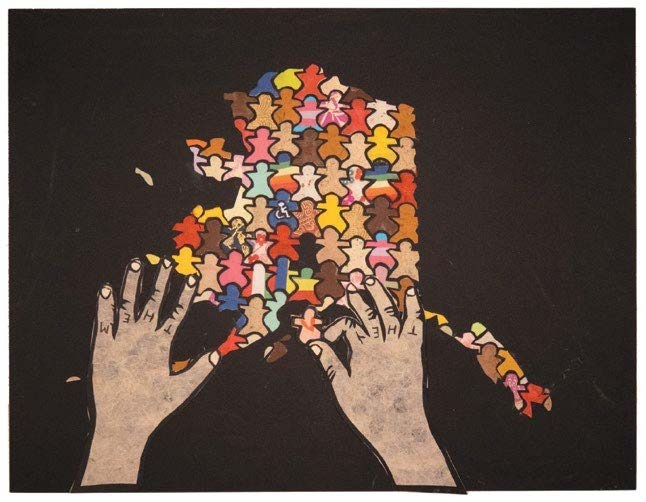

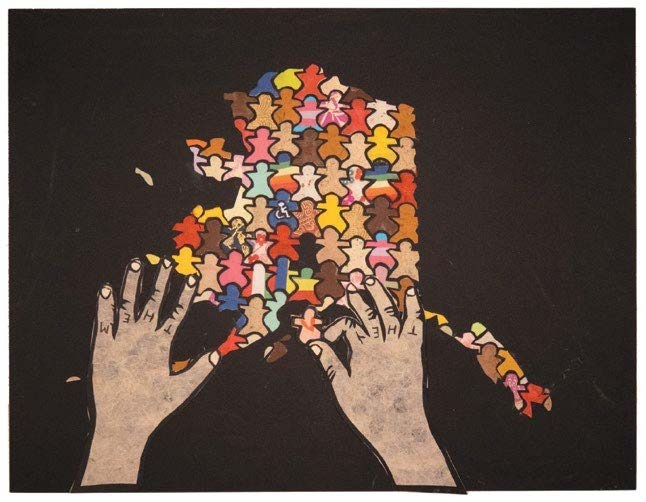

(MISS)REPRESENTATION, By Desiree Hagen. Handmade and commercial paper, 19”x25”.

(MISS)REPRESENTATION, By Desiree Hagen. Handmade and commercial paper, 19”x25”.

by Elizabeth Earl, Desiree Hagen, Nancy Lord, Winter Marshall Allen, and Chloe Pleznac

Winter 2021-22, FORUM Magazine

This essay was written as part of the Forum's Community | Media | Possibility programming, which explored the roles, responsibilities, and relationships between media and community. Five community members with an interest in local media formed the Kenai Peninsula cohort through the Journovation fellowship. As an example of what might serve as community or collaborative journalism, they offered this co-written article presenting multiple perspectives in dialogue together.

IN A RECENT PODCAST, journalist Ezra Klein and writer George Saunders talked about “relocalizing” politics. Klein argued that “our local political systems have weakened, have withered. And that’s often because we don’t consume media that attaches us to local fights, local questions.” If Alaskans are getting their news from cable TV networks or the New York Times or a talk radio show from Georgia, they are not only filling up on information that may feed their own biases, but also on information that focuses on national politicized issues that further divide us. His advice was to “work on your own informational ecosystem to attach yourself to things that are local.”

Saunders offered that if people of different political beliefs shared local news, like a need for road repair, they could not only reach agreements about what to do but would be participating in “something democratic, and communal, and positive.”

Our state is large and diverse, with equally large and varied challenges specific to individual communities. Who knows the people, histories, and issues of our communities better than the writers, broadcasters, and photographers living in them?

So—community media. What is its role in Alaska, on the Kenai Peninsula, and in Homer? How can it enhance our “informational ecosystem” by involving more voices, more viewpoints, more participation by readers, viewers, and listeners? An ecosystem, to be healthy, needs diversity, stewardship, and integrity. It needs its inhabitants to relate to one another, to respond to changes, to recognize that they are all a part of the system and can solve problems together.

What is our community media ecosystem on the western Kenai today? Largely, it’s our newspapers and radio stations—two newspapers, two public radio stations, and several private radio stations. Each has its own niche, style, and content. News consumers also rely on newsletters of various sorts, and—of course—social media. Together these present “hard news” (the city council did “x”), “soft news” (art show openings), breaking news (avalanches and road closures), interpretations and opinions, and entertainment. This is the “news,” the shared environment in which we live together, the common ground for understanding the world around us. This connection is powerful in a place where distance and isolation are significant factors affecting community cohesion.

We also enjoy, increasingly, collaborations among the media and between the media and other organizations. Public radio is part of a statewide system, and the local stations also collaborate with various nonprofits. Our newspapers share reporters and news feeds with “sister” publications. Local media encourages opinion pieces of all sorts from local people. All media increasingly rely on internet platforms to curate and extend their news coverage.

(MISS)REPRESENTATION, by Desiree Hagen

Handmade and commercial paper, 19”x25”

One thing that Community | Media | Possibility made me realize is the importance of WHO is telling the story and HOW these stories are told. As an artist and media producer (I produce a podcast on gardening and agriculture in Alaska, called Homer Grown), I think about this constantly. I created this piece after a trans friend was misgendered and deadnamed. Hearing their frustration affected me; beyond a genuine mistake, the misgendering incident they described seemed intentional. I couldn’t understand how someone could consciously choose to deny my friend these aspects of their identity. I think about this similarly with journalistic representation. While I am not trans, in my art and work my goal is to make a conscious effort to both convey a message with equity and to present a fair representation, especially if I am portraying someone with a gender identity, sexual orientation, race, or community that is different from my own.

With fewer opportunities in or with the media, fewer voices are heard, and many, many stories of importance go untold and unexamined.

Could our media do more to build a richer, lovelier ecosystem? Of course. What media person doesn’t dream of having the resources to bring together more voices, to reach deeper into stories that need more context, to find and tell the stories that have been obscured by louder noises? Budgets, personnel, time—these all are limiting factors.

Specific to our region, the number of newspaper reporters has decreased from a solid dozen to just two or three, and one paper—the Homer Tribune—has been eliminated. The reductions in radio news staff are similar. Fewer reporters on the ground, especially when they must also manage online presences, means less coverage and less depth to that coverage.

All communities are divided among socioeconomic, cultural, and political lines, but in Alaska these differences can be exaggerated. Representation of all sectors is difficult for even a robust media, and those who feel they are unrepresented (or unfairly represented) can distrust, resent, and reject the media.

With fewer opportunities in or with the media, fewer voices are heard, and many, many stories of importance go untold and unexamined. The loss of local coverage, including analysis, results in less consideration of those issues closest to our daily lives—schools, roads, taxes, snow clearance, and community events. Without broadly sharing what happens in a community, members become poorly informed, isolated, and unlikely to join together in problem solving. In short, they no longer share a common environment.

The Pew Research Center last year found that 86% of Americans get news from their digital devices, a higher portion than get it from TV and a much higher portion than get it from radio or print. When asked about their preferences, 52% prefer digital, while 35% prefer TV and only 7% and 5% prefer radio and print, respectively. The numbers skew even wider by age, with younger people greatly preferring digital and, among digital choices, preferring social media to news sites.

Similar data may not exist for Alaska, but we know that Alaskans’ social media reliance for news likely tracks the national trends.

The Pew data, moreover, shows that “Americans who primarily turn to social media for political news are less aware and knowledgeable about a wide range of events and issues in the news [and] are more likely than other Americans to have heard about a number of false or unproven claims.” Social media pushes people toward slanted news sources that confirm their existing biases and, moreover, tend to be oriented toward national politics.

Local media, ideally, works with—collaborates with—the community in which it lives.

What does this mean for media and community in Alaska, the Kenai Peninsula, and Homer? Are our local news organizations doomed, as our municipal governance, community celebrations, and personal stories go unreported and unexamined? Or, can we work together, in a world of information kudzu, to use all the tools of our modern, changing world to maintain an ecosystem that includes us all and works to solve local problems?

First, some responsibility goes to the news organizations themselves, which would benefit from embracing the ways people consume news while balancing their need for revenue. That means reaching out to community members, beyond just subscribers, to understand how people consume their news. Drawing on the talents of a wider range of writers, video and audio producers, and artists for content on existing platforms may increase trust and broaden interest. More community connection among news producers and news consumers will strengthen relationships and participation.

Our community (along with the rest of our country) also needs to invest in news literacy. That starts with the schools, which must include curriculum on news literacy. Students should be leaving high school with a complete set of skills to be able to evaluate news articles and videos for validity, value, perspective, bias, and source material.

On an individual basis, one thing we can all do to be part of “something democratic, communal, and positive,” to use Saunders’ encouraging words, is to support community media. Not just by consuming it, but by joining, subscribing, and paying for underwriting or advertising. We can contribute a voice with a letter, an op-ed, a freelance article, a tip to a reporter, a call about a need in the community; we can encourage others to do the same. Kind or at least civil comments, constructive criticisms, and other forms of engagement are vital to keeping media centered on what is truly necessary and needed for the health and future of the community.

Local media, ideally, works with—collaborates with—the community in which it lives. The community, ideally, participates with the media, as consumers and, when possible and appropriate, as partners in supporting and presenting the concerns, values, and positive ways of strengthening our society at every level.

Think again of our media ecosystem. Do we want it to become a monoculture, like a corn field or a plantation forest, or do we want to live in a healthy ecosystem with the richness of variety, inclusion, and connection? ■

The Alaska Humanities Forum is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that designs and facilitates experiences to bridge distance and difference – programming that shares and preserves the stories of people and places across our vast state, and explores what it means to be Alaskan.

February 16, 2026 • Colleen Lomenick

January 28, 2026 • Polly Carr

January 20, 2026 • Shoshi Bieler